What is one of the first stories we learn as children of Western culture? The cautionary tale of Adam and Eve’s banishment from Eden, a story that sets us fretting, evoking fears of abandonment and loneliness, worries about identity and belonging. So we get our first taste of what happens when we lose our sense of home.

When we speak about home, we usually mean a physical place, a dwelling, a place of shelter or refuge. But home also has a symbolic meaning: we are at home in a particular landscape: forest or mountains, desert or beach. We are at home in a nation, on a continent, among others who share our values, our language, a cultural context. Our bodies are also our homes, spirit and soul, mind and heart. To be at home in one’s body is to feel one’s authentic and whole self, our flesh and blood animated with the invisible aspects of Being.

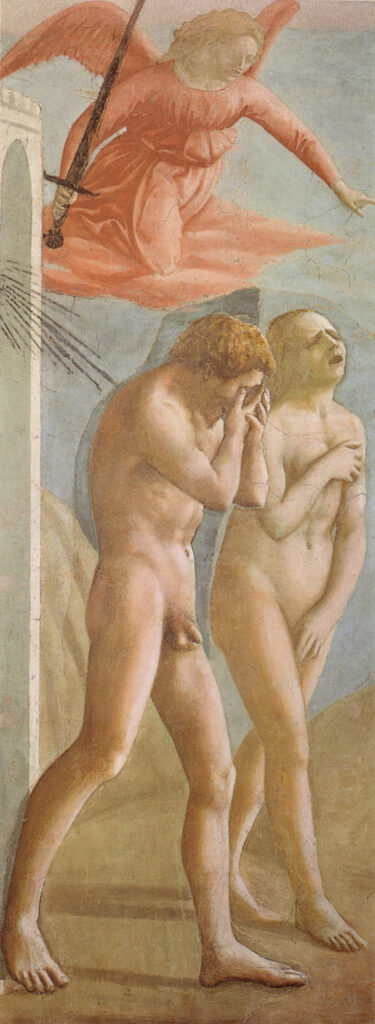

For the sin of seeking knowledge, the God of the Old Testament pointed His finger at Adam and Eve and expelled them from paradise to wander the earth in exile. Many great artists have envisioned on canvas the ravaged faces of the mournful couple. When we stand in front of these paintings, we are struck with a primal feeling of sorrow, the ping of our own fear of desertion and displacement from home.

For the sin of seeking knowledge, the God of the Old Testament pointed His finger at Adam and Eve and expelled them from paradise to wander the earth in exile. Many great artists have envisioned on canvas the ravaged faces of the mournful couple. When we stand in front of these paintings, we are struck with a primal feeling of sorrow, the ping of our own fear of desertion and displacement from home.

Famine, climate change, natural disasters, political violence, and governmental upheaval uproot thousands from their homes and homelands and force multi-generational populations to undertake arduously dangerous journeys to find a new home. The Jungian analyst John Hill tells us that the loss of home is a quest for identity. As he writes in At Home in the World: Sounds and Symmetries of Belonging, “As home is intrinsically connected to a sense of self, its loss may have devastating effects on people’s lives.”

My friend Myron Eshowsky, M.S., an expert in working with refugee and marginalized populations, most recently Syrian refugees in Jordan, suggests that “historical trauma is remembered in the land.” What is missing from the discussion of treatment for communal and personal trauma is an understanding that as “citizens of the earth,” we are extensions of the landscape we call home. Eshowsky writes, “When a sense of home is upset . . . individuals and communities may exhibit what may be commonly understood as psychological trauma, but the root of their experience—and healing—may call for the inclusion of place and all it can hold.”

In a paper titled “Place, Historical Trauma, and Indigenous Wisdom,” Eshowsky tells the story of a healing ritual on the site of the now-demolished building in Milwaukee where years earlier serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer committed macabre acts of dismemberment and murder. “The sense of death at the site was overwhelming,” he writes. The lot was barren and devoid of living plants. In a communal prayer accompanied by a priest, the family of victims and neighborhood people joined with tears and prayers in shared grief. The blessings included a wish for the land to return to life. A year later, flowers and grass were poking up through the rubble.

In a paper titled “Place, Historical Trauma, and Indigenous Wisdom,” Eshowsky tells the story of a healing ritual on the site of the now-demolished building in Milwaukee where years earlier serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer committed macabre acts of dismemberment and murder. “The sense of death at the site was overwhelming,” he writes. The lot was barren and devoid of living plants. In a communal prayer accompanied by a priest, the family of victims and neighborhood people joined with tears and prayers in shared grief. The blessings included a wish for the land to return to life. A year later, flowers and grass were poking up through the rubble.

The lucky among us who have been not compelled to flee and resettle are faced with a different kind of loss of home. The landscapes we have grown accustomed to, the daily landmarks that were once as familiar as our own hands, have disappeared. The grocer on the corner has gone out of business, as has our favorite pizza parlor, barbershop, and drug store. Our toddler’s daycare center has shut its doors. Where raging fires have consumed the earth, entire towns have vanished, the woods we once hiked turned to ash. Floods and hurricanes have remade our beaches; new apartment complexes are springing up to replace old neighborhoods of duplexes and one-family homes.

Is it any wonder our bodies, our most intimate homes, are reacting to these dramatic and swiftly occurring events? Home is a felt reality as well as a physical reality. Consistency, reliability, attachment to beloved objects and persons are essential aspects of our well-being. When we feel groundless and distressed, our bodies display physiological markers of stress. Currently, we are plagued not only with the COVID virus, but with elevated blood pressure and blood sugar, restless nights, depressed and anxious moods. Our minds struggle to rise clear of a perpetual fog. Like other animals who have experienced a change in habitat, we respond.

Since the pandemic, our homes have become the site of both our public/work/social lives and our private/domestic lives. Paradoxically, while we may be spending more time in our homes, we are less “at home” in the world.

What does it mean to be more at home in the world? How can we create a sense of belonging and identity despite our rapidly changing environment? One way is to enlist our imagination. “Home” is rooted in our core self as memories, dream images, reveries. Home is linked to kinship bonds, to the landscapes of our origins, to collective archetypal patterns that exist at a level of being unaltered by external circumstances. These foundational archetypal patterns are like secret treasures buried within.

What does it mean to be more at home in the world? How can we create a sense of belonging and identity despite our rapidly changing environment? One way is to enlist our imagination. “Home” is rooted in our core self as memories, dream images, reveries. Home is linked to kinship bonds, to the landscapes of our origins, to collective archetypal patterns that exist at a level of being unaltered by external circumstances. These foundational archetypal patterns are like secret treasures buried within.

French philosopher Gaston Bachelard in his book, The Poetics of Reverie: Childhood, Language, and the Cosmos, argues that reveries carry us back to our childhood. He writes, “childhood remains within us {as}a principle of deep life, of life always in harmony with the possibilities of a new beginning. . . From our point of view, the archetypes are reserves of enthusiasm which help us believe in the world, love the world, create the world.”

We can revisit images of home and well-being through guided meditations. We can imagine ourselves walking along the river path of our ancestors. We can imagine ourselves in the treehouse where we spent time as a youth. We can choose a special tree or rock or sit in a garden and imagine roots growing from our heels into the hot magma at the center of the earth to which we belong. We can embrace the belief that we are never without a home because we carry our home inside us.

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at