A Conversation with Neuroscientist Daniela Schiller

Part Three of a three-part interview. Read Parts One and Two.

Large swaths of populations, including Americans, are experiencing the devasting effects of trauma. To honor this epidemic, to offer new insights into its mechanisms, and to inspire hope for the reduction of human suffering, I extended my interview with Daniela Schiller, Professor of Neuroscience and Professor of Psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai Hospital and Director of the Schiller Laboratory of Affective Neuroscience.

Dale Kushner: Can someone suffer the effects of a traumatic memory, but be unaware of the event that caused it? If someone had trauma, but doesn’t remember it, what’s going on?

Daniela Schiller: A lot of what is happening in the brain is unconscious. We have learnings that we are unaware of. We can have events that impact our behavior such that when there is a trigger, we’ll respond in a certain way, but we won’t remember the association that formed it. A simple example is phobia. People are afraid of flying, but it wasn’t always because of a traumatizing event. The same is true with phobias about snakes or blood. The heart of these could be some event that they’re unaware of. There are events that shape our behavior, that make our behavior habitual or strongly associated with something without our awareness.

DK: But if your research is about eliminating or muting the negative feelings and someone doesn’t know the original trauma, how could they be helped?

DS: There are several lines of research, like the research on reconsolidation, the idea that you have to reactivate a memory in order to modify it. Also, the research that we’ve been discussing, that traumatic memory is an experience of the brain as if it’s happening in the present[1] These point to the fact that a memory, in order to be modified, has to be active and engaged with. At the same time, there are other ways to approach behaviors when their source is unknown — by analyzing the behavior. Even if we think we know the source, we don’t always necessarily know, because sometimes we can have a memory that is very disturbing for us, or a focal event, which very well can be not accurate or was revised or reconstructed over time.

The interesting thing is that now there’s growing research on the effect of psychedelics in treatment for PTSD and other conditions like depression. What people are reporting is that while they are on this psychedelic trip, many memories come up, memories that they didn’t know they had, memories they never linked. So there’s an event and suddenly there are additional peripheral events like, oh, and then you make new connections, and that suddenly makes the memory either more understandable or frames it differently. That type of flexibility seems to be occurring in research on psychedelics. When you don’t have that, that could be part of the rigid response or not necessarily accurate response that you have to a particular event that you think you remember.

The interesting thing is that now there’s growing research on the effect of psychedelics in treatment for PTSD and other conditions like depression. What people are reporting is that while they are on this psychedelic trip, many memories come up, memories that they didn’t know they had, memories they never linked. So there’s an event and suddenly there are additional peripheral events like, oh, and then you make new connections, and that suddenly makes the memory either more understandable or frames it differently. That type of flexibility seems to be occurring in research on psychedelics. When you don’t have that, that could be part of the rigid response or not necessarily accurate response that you have to a particular event that you think you remember.

DK: What determines the severity of the effect of trauma? We know that some people who have experienced severe trauma don’t seem to be affected while others who have had less severe trauma, or maybe just bad experiences, seem to be very altered by them.

DS: Yes, that’s interesting because the definition of the trauma is not in the event itself. You don’t compare events, you compare the responses to the events. That’s why there’s no competition between someone who was at 9/11, for example, close to the building versus far from it but with a different interaction. There’s no measure like that. It’s all in the response. The definition is: to what extent does a trauma affect your daily life and functioning? If it impairs functioning — this is the measure of the severity. If you can’t get out of bed, if you don’t interact, you can’t work, you don’t need — these are the degrees of severity, how it affects you at that personal level.

DK: Are some people more vulnerable? Who is more likely to be affected? Can we predict who will be affected?

DS: Yes, some people are more naturally resilient than others. Many factors come into play. One is the past, like childhood trauma. The other could be genetics. Some processes make your brain more sensitive. The way the brain reacts could lead to some processes versus others, like epigenetics, which is the experience of your parents. We see this in studies of the second generation of Holocaust survivors, and also in animals. If the parents were stressed, then the pups, the offspring are also more reactive or more sensitive to negative experiences. This is because of the way the genes are being monitored, what is being inherited. In this sense, experience is being inherited. It’s also about the context. In what conditions do you have social support? Many parameters will influence resilience.

DK: Which is more important: the intensity or the duration of the trauma?

DS: These all come into play. The intensity, the duration, and also the age of the memory. In the present moment, each of these can have a serious effect on trauma. There are traumas that are one-time events, and there are traumas that are very much chronic or prolonged. These are complicated types of trauma. They are different from a one-time trauma. So now you get into the different forms that trauma can take, and each one comes with its own characteristics and complexities.

DK: Can someone who has inherited the epigenetics of a traumatized parent change their epigenetics, if intervention is early enough?

DS: Yes, I would expect so. It is not my research, but in principle what epigenetics means is that you have the DNA, but peripheral factors affect which gene is being expressed. They’re like the monitors, the modulators of the genes that you already have, and some of them will be expressed more or less depending on your experience. What is shaping the next generation is the environment in the fetus when the fetus is evolving. This is where epigenetic factors come into play, what is formed in the growing fetus of the next generation. Whatever is in that environment at the time of the pregnancy will have an effect. If you did have a negative experience, but then it was mitigated, this will have an influence because epigenetics is about the environmental and experiential context of your development.

DK: One last question. Where are you headed now with your research? What are you excited about?

DS: I’m excited about diving into complexity, diving into experiments that touch on personal experience. They’re difficult to study in the lab, which has to be very controlled. With new methods of analysis and also with artificial intelligence, machine learning gives us approaches to study more complex processes. I hope science will become more personal in the sense that it could characterize and be able to focus on the individual. Science is usually about statistics in large groups, and you need large samples to see effects, but I am hoping we can explore it more at the individual level.

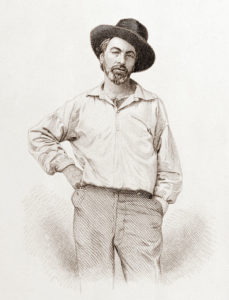

For artists and scientists, their goal is to understand experiences in life. Their goals are exactly the same, and even as specific. If your character in the novel you’re writing is struggling with a certain memory, it’s a very specific sliver of reality you are trying to capture. I think science is trying to do the same.

[1] O. Perl, O. Duek, K. Kulkarni, C. Gordon, J. H. Krystal, I. Levy, I. Harpax-Rotem, D. Schiller, “Neural patterns differentiate traumatic from sad autobiographical memories in PTSD,” Nature Neuroscience, 26, 2226-2236 (2023); Published November 30, 2023.

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

If you found this post interesting, you may also want to read “How the Brain Stores Traumatic Memories,” Part One of three conversations with Daniela Schiller, “Memory and Trauma: We Are More than What We Remember,” Part Two of three conversations with Daniela Schiller, and “Recognizing and Healing Inherited Trauma,” an interview with Rabbi Dr. Tirzah Firestone.

Keep up with everything Dale is doing by subscribing to her newsletter, Exploring the Unknown in Mind and Heart.