Your Dreams Know More Than You Do: Are You Listening?

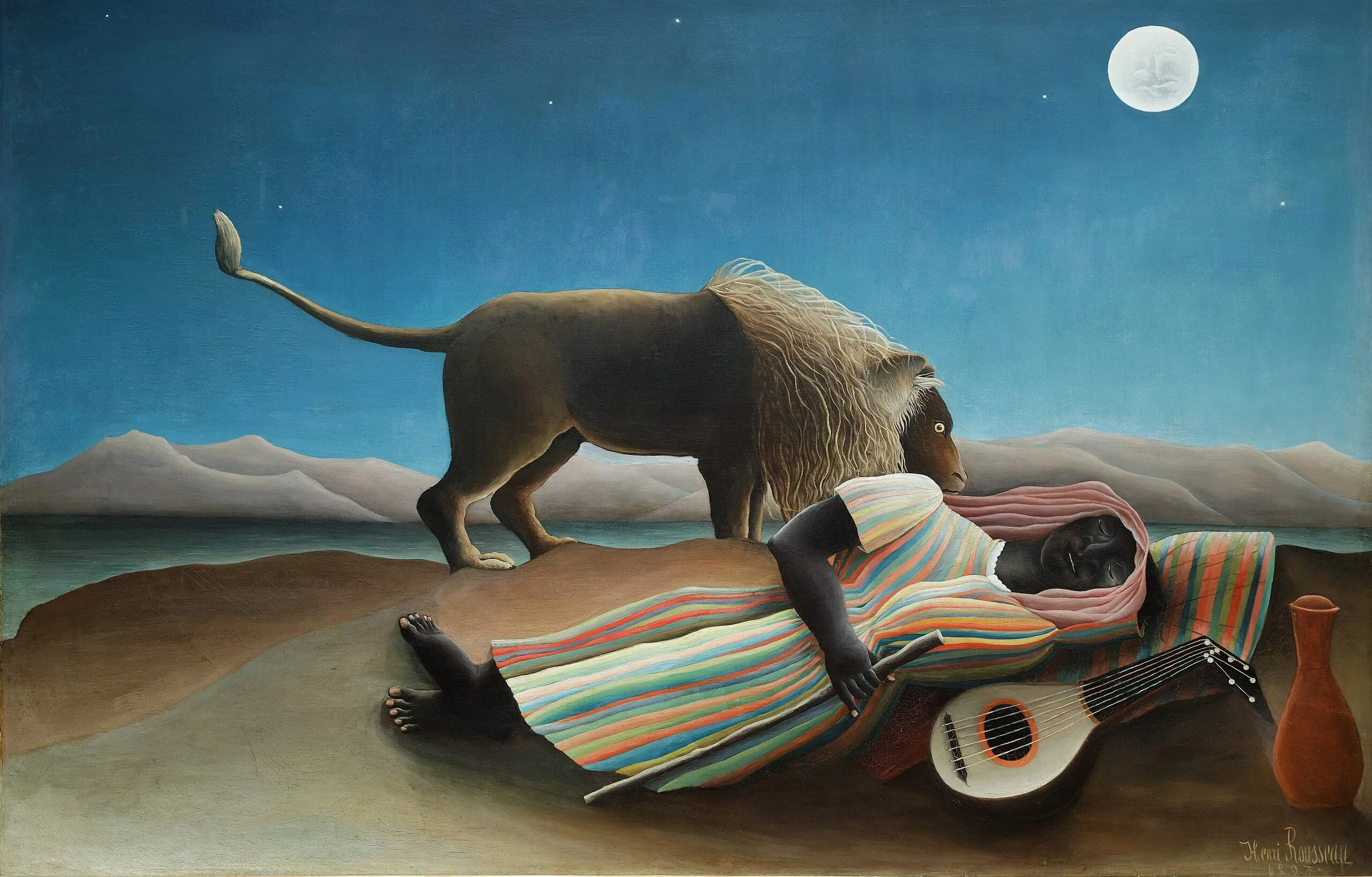

Image: The Sleeping Gypsy (1897) by Henri Rousseau (1844-1910). Museum of Modern Art / Public Domain

Most of us spend a third of our lives asleep, twenty percent of those hours dreaming. Babies dream, the elderly dream, all of us between infancy and old age dream.

Our dream life is mysterious and has captured the fascination of humans since the beginning of recorded history. Theologians, psychologists, psychiatrists, anthropologists, sociologists, artists, writers, musicians, philosophers and populations around the world have delved into their mystery. In the ancient world, dreams were a source of divination, examined to predict and sometimes forestall future events such as illness, famine or war. We associate Sigmund Freud and modern psychoanalysis with codifying a method of dream interpretation, but the earliest written record of an interpretation of dreams comes from well before the time of Moses, in Mesopotamia, where dreams of important people were inscribed on clay tablets in cuneiform. In The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2100 BCE), Gilgamesh’s mother interprets his dream about a falling star as foretelling his meeting with a strong companion (Enkidu).[1] Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians and Greeks believed dreams were direct revelations from the gods.

Where are we when we dream? Where do dreams come from? These questions continue to puzzle us. Dreams appear to be as real and palpable as waking reality, and yet we know they are not part of our day world. How should we relate to these vivid images and the stories they tell?

Dreams speak to us of the past, present, and future. Forgotten memories, friends of our youth, places we’ve visited, former pets and future children come unbidden in the depth of sleep, reminding us literally and symbolically of who we have been, who we are, and who we might become. They alert us to our inner world. If we dream about our child self, the dream may be referring to an actual childhood event or to an inner subjective state, the child within us still, her wishes, longing, and fears, separate from our conscious egoic self. The child image may symbolize a state of innocence or the birth of something new, a new opportunity or a new attitude in our lives. A dream about our mother may signify our actual mother, the mother we may become, a maternal attitude toward someone or something, or a need for mothering.

In their now classic book, Dreams, A Portal to the Source, Jungian analysts Edward C. Whitmont and Sylvia Brinton Perera write, “Solving a problem only in dream is not sufficient. An equivalent activity in waking life must still follow…It requires our living with the images and messages and attempting to work with them responsibly and realistically in daily life.”[2]

In waking reality, we use our five senses to interact with the world. When we sleep our minds are active but not tied to our senses. In our dreams, we may be flying over treetops or eating pancakes with a dead relative. These experiences feel entirely real, but they are only occurring in a non-physical dream reality. In the realm of dreams, the laws of physics do not apply. We can walk through walls, grow a tail, or speak foreign languages we’ve never studied.

For the modern dreamer, dreams can be allies in fostering spiritual, emotional, and physical well-being. Indigenous cultures and many spiritual traditions as well as the depth psychology work of Carl Jung treat dreams as a tool for greater self-awareness and enlightenment.

A person working with their dreams might ask for a dream that offers guidance on a specific problem in waking life or to connect with an ancestor or someone else from the past. The dreamer is encouraged to ask a question of “the dream maker” before going to sleep such as “Where am I now in my life?” and hope for a dream that illuminates an answer.[3]

Science gives us another way to understand why we dream and what is going on when we do. Ongoing neuroscience research provides explanations and physical models for our dreaming brains. We know that each stage of sleep, including REM sleep when most dreaming occurs, is important for optimal cognitive functioning. The three major scientific theories on why we dream are 1) that it helps us consolidate memories, 2) that it has provided an evolutionary advantage, and 3) that it helps us process emotions. Some researchers believe dreaming helps our brains sort, store, and discard memories, essentially decluttering our brains each night.[4] An evolution theory proposes that dreams may help mammals remember, rehearse or find solutions to difficult or threatening situations in waking life.[5] REM sleep may also help us regulate our emotions to recover from stress, to strengthen emotional resilience, and to resolve emotional concerns with significant people in our life.[6],[7]

Researchers have recently reported significant breakthroughs in lucid dreaming which have received lots of attention.[8] Lucid dreaming is a dream state in which the dreamer realizes they are dreaming during a dream. In non-lucid dream states, the dreamer is not aware they are dreaming. Lucid dreamers are often able to control aspects of their dreams, interrupting nightmares and restoring a sense of well-being by replacing frightening dream images with more beneficial ones. Currently, lucid dream therapy is being used to treat anxiety and PTSD by lucidly interrupting a nightmare and reimagining the threat in a way that ends the traumatizing element of the event”[9]

Working on understanding and honoring our dreams can bring new energy to our lives and a greater sense of integration. Life demands we continue to adapt and renew ourselves. We face uncertainties, physical challenges, paradoxes, and sorrows. Especially during times of rapid change and turmoil, dreams can be our friendly guides by alerting us to what’s brewing in our unconscious minds and offering revelatory clues on how to move forward with greater wisdom.

Isn’t it time for you to start a dream journal? Don’t you wonder what your dreams are trying to tell you?

[1] David, Gerald J., The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation, (2014) Insignia Publishing

[2] Whitmont, Edward C. and Perera, Sylvia Brinton, Dreams, A Portal to the Source. (1989) Routledge. p. 78.

[3] Ward, John T., “Dream Knowledge—Understanding the Dreamworld Utilizing the Medicine Wheel,” Journal of Global Indigeneity, December 8, 2023

[4] Bloxham, Anthony, and Horton, Caroline L., “Enhancing and advancing the understanding and study of dreaming and memory consolidation,” Consciousness and Cognition, August, 2024.

[5] Garver, Noah, “Cognitive and Evolutionary Theories of Dreaming,” Social Science Research Network (SSRN), August 24, 2023.

[6] Huberman, Andrew and Walker, Matt, “The Science of Dreams, Nightmares, and Lucid Dreaming,” Huberman Lab podcast, May 8, 2024.

[7] Zhang, J., et al, “Evidence of an active role in dreaming in emotional memory processing shows that we dream to forget,” Nature, April 15, 2024

[8] Carr, Michelle, “The New Science of Controlling Lucid Dreams,” Scientific American, December 17, 2024.

[9] Cherry, Kendra, “Four Techniques to Achieve Lucid Dreams Tonight,” verywellmind, February 24, 2025

If you found this post interesting, you may also want to read: