A conversation with Jungian therapist and rabbi Tirzah Firestone about epigenetics and recovering from trauma

Today I’m delighted to welcome Rabbi Dr. Tirzah Firestone for another information-packed conversation together. (See “Inherited Wounds: Tirzah Firestone on Ancestral Healing” and “Recognizing and Healing Inherited Trauma” for our earlier conversations).

Dr. Firestone is a Jungian analyst, rabbi, and the daughter of Holocaust survivors, whose research is on recovery from trauma, including the mechanisms of inherited trauma. In the revised edition of her deeply wise book, Wounds into Wisdom, Dr. Firestone draws on the latest neuroscientific and psychological findings, interweaving them with compelling stories of trauma and healing, to offer readers hope, understanding, healing, and the means to discover how suffering can be transformative.

Dale Kushner: There is a lot of new biology out there that is changing how we think about health, lifespan, trauma, and our genetic inheritance. Your recent book explains this in a way that I found very accessible to non-scientists. Can you give us an overview here?

Dale Kushner: There is a lot of new biology out there that is changing how we think about health, lifespan, trauma, and our genetic inheritance. Your recent book explains this in a way that I found very accessible to non-scientists. Can you give us an overview here?

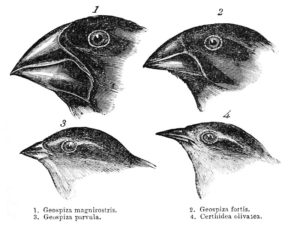

Tirzah Firestone: There is a lot of fascinating research going on. The last ten years have given us much more insight into the growing field of epigenetics, which studies the impact of life’s stresses on our genes’ activities.

We used to think that our genes were the major determinant of our health, our lifespan, the diseases we would get, etc. Now we know that our genes are incredibly responsive. They answer to the environment in which we live. Depending on our stresses, there are a host of epigenetic mechanisms that turn our genes on or off. Scientists call this gene expression.

So, for example, if you are living through a war, or have lost your home, or a parent dies, or some other traumatic life event is occurring, your genes will adjust to these environmental stresses by means of epigenetic mechanisms that act on (epi means upon or above) the chromosomes. They tell the genes what to do.

Epigenetics draws on clinical studies with mice and rats, demonstrating that stress and struggle can imprint not only on us but upon future generations. For example, early nurturing patterns by the mother, for example, have been shown to pass to grand-pups and great-grand-pups, even when they had never interacted.

In a study from Emory University,[1] mice were exposed to a sweet smell, acetophenone, and then received an electric shock to their feet. Associating the two, whenever the mice smelled the smell, they became fearful and froze. Amazingly, their offspring—even the grandpups who had never met their grandparents or been exposed to the smell or shock—showed panic in the presence of the smell.

These offer evidence for what many of us have been intuiting for a long time, that stresses and traumas experienced by our ancestors influence us, say in our resilience or lack thereof, several generations later.

But epigenetics also speaks to the impact of socio-economic stresses on entire ethnic groups. Moshe Szyf, a very prolific epigeneticist, shows how gene expression differs among those who grow up well-off vs. those who grow up disadvantaged, making the latter group more vulnerable to a host of diseases and shortened life spans.[2]

DK: Your own research is on recovery from trauma. Can you tell us about your study and findings?

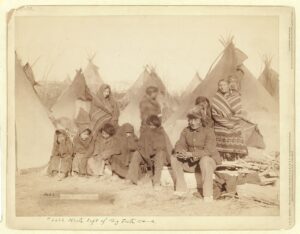

TF: My study was on Jewish people from around the world who had gone through extreme traumas such as war, racial and religious discrimination, the loss of a child to terrorism, and such. My focus was on those who were able to go through the many stages of healing and integration and come out transformed by their traumas.

I discovered among all of them strong common denominators. But there is no one formula for trauma healing! Every one of us has a unique trajectory for our healing. My thirty years of experience in the healing field tells me that human beings are intrinsically primed for healing. We get directives from the inside that tell us what we need to do to work through our traumas and come back into full life.

DK: Can you share with us today the seven principles that emerged from your research?

TF: Yes, I’d be happy to. These are common denominators that I found in my research subjects who thrived again after their tragedies, having transformed their lives.

- Facing the loss

More than anything else, directly facing our losses initiates the process of healing. This first principle means resisting our friends’ well-intentioned urges to get back to work or “get on with life.” We must give ourselves the gift of time and ride the waves of our pain.

- Harnessing our pain

Once we face our losses, we may encounter intense pain. Because trauma disconnects us from our bodies, there’s a tendency to numb out. The alternative is to re-inhabit our physical selves. Physical exercise and self-care are paramount here. Pain made conscious can turn into fuel.

- Finding new community

We may find ourselves changed by our trauma, feeling that there is no going back to how we used to be. Now we have to find people who understand us. Because traumatic experiences often leave us with a sense of shame or isolation, finding authentic connections with people who can hear and hold us compassionately is essential. The people I worked with felt a need to build a new social network, to find other like-minded people.

- Resisting the call to fear, blame, and dehumanize

Unprocessed trauma can leave us permanently defensive. The human tendency to “other” people around us is the obvious next step. But that leaves us isolated, self-righteous, and lonely. Those who do the hard work of healing their traumas succeed in melting the walls of separation and resisting hatred for those who hurt them.

- Disidentifying from victimhood

One of the main keys to trauma recovery is agency, the inner sense that we are in charge of our own lives, and we can shape their outcome.

- Redefining specialness

One of the legacies of trauma can be the feeling that we are different, alone, and separate. But these feelings can flip into their opposites: feeling special, chosen, superior, for what we have gone through. One of the most important takeaways from trauma healing is that human beings are interdependent, that our healing depends on one another.

- Taking action

Trauma recovery means facing what has happened directly and deeply mourning our losses. Then—and for each person there is their own internal timing—some kind of work or meaningful action in the world emerges.

DK: Our interview will be appearing around the holidays and just before the new year. Do you have any special advice for readers at this time of year?

DK: Our interview will be appearing around the holidays and just before the new year. Do you have any special advice for readers at this time of year?

TF: Yes, holidays can be a particularly challenging time of year, especially for those of us who are raw from losses and traumatic upheaval. We are often bombarded by family or lack of family, outward cheer that doesn’t match our inner felt sense, and so many distractions that pull us out of our own inner experience. Take alone time to feel your feelings, journal, take walks, move your energy to let off steam, and avoid excesses like sugar, alcohol, or recreational drugs that unground you. Main point: This is the time for doubling down on our self-care. Stay in touch with yourself and lead with self-compassion!

References

[1] Dias, B. G. and Ressler, K. J. (March, 2014). “Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations.” Nature Neuroscience 17:89-96

[2] Nada Borghol, Moshe Szyf, et al., “Associations with Early-Life Socio-Economic Position in Adult DNA Methylation,” International Journal of Epidemiology 41, no. 1 (February 2012): 62-74

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at